I’m moving my blog over to asocial.substack.com. I’m going to focus more on inequality issues and summaries of interesting social science work. Hope you enjoy it!

ChatGPT is amazing as long as you already know the answer

Too much has been written about ChatGPT. It’s an extraordinary piece of technology that lets you describe how to recode a variable in Stata in the poetic style of Sir Gawain the Green Knight. Folks have discussed the many situations where ChatGPT is extraordinary and where it falls short. I thought I’d share one exercise that illustrates its shortcomings.

I thought that perhaps it would be a good source to identify answers for when and where specific pieces of legislation were passed. These should be part of the training data ChatGPT uses, and law passage either did or didn’t happen. So we shouldn’t be in the realm of bullshit and right in this technology’s wheelhouse.

I occasionally write about Right to Work laws, and so thought I’d use these as a test case. There are two states that prove problematic: Texas and Indiana. Indiana briefly passed Right to Work from the mid 1950s to the early 1960s. They then repealed the law, only to pass it again in 2012. Texas functionally passed Right to Work in 1947 (see https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/Housejournals/50/03041947_29_600.pdf, page 610 for the Rep side). In 1993 Texas made some major adjustments to the law, formalizing it and fleshing it out. But I think you’d have a hard time arguing that Texas did not have Right to Work prior to 1993 (some pro-RTW websites list Texas as non-RTW until 1993).

I asked ChatGPT about the timing of Right to Work passage. Here’s what happened.

A few things:

In simple cases, like Florida, ChatGPT was correct.

For Indiana, ChatGPT twice claimed with confidence that Indiana had no RTW law prior to 2012. It was only when I corrected it with my own pre-existing knowledge that the program updated its claim. I’m not sure why it would state with certainty a claim that was obviously false, especially since it seems like it had the specific information in its database. If I didn’t know that Indiana passed RTW briefly in the 1950s, I think it’d be reasonable to think this state was a simple case like Florida. And I’d come away with an incorrect understanding of the world.

Look at the hard pushback regarding Texas. Even when I cite a great article by Marc Dixon, ChatGPT does a funny dance: “I’m so sorry. You’re right and I’m wrong. Texas followed your argument, although I, ChatGPT remain correct and Texas had no RTW until 1993.” That’s super weird. It makes me wonder if I could do similar pushbacks with incorrect information and get the same equivocating answer: “I’m so sorry, you’re correct, Washington State has been a RTW state since 1945, although the state has no RTW law. I’m sorry for my error.” I also wonder why it’s so adamant to stay with its, at best, questionable answer.

Whether or not a state passed a Right to Work law is pretty cut and dry. I admit that the Texas case is quite ambiguous, but I don’t see how you could not look at the link I posted above or the article I cited in the chat and not think, “OK, Texas definitely had everything that is RTW passed in 1947, perhaps with a different name.”

I think this is a pretty serious issue for ChatGPT. Whether a law passed or not is exactly the kind of knowledge and answer set that this program should be ideally used for. This really kicks out one of the main benefits of this program for me. Folks have described it as a master bullshit generator, and I really think that’s true. Unless you already have the sufficient stock of knowledge to assess its answers, don’t use ChatGPT to learn about true/false pieces of history.

The Labor Movement isn’t Reinvigorated

The BLS maintains data on work stoppages. The big point is that there isn’t a labor movement, and there hasn’t been for some time. I keep hearing hopeful statements about labor’s reinvigoration, whether about Starbucks or Amazon or the Railroads. But I just don’t see it.

Below is private sector union membership over time

Union Membership declined from about 1/3 of private sector workers in the 1950s to about 6% today. There’s no evidence of any uptick in the last few years.

Let’s look at work stoppages

BLS keeps track of large work stoppages, I think 1000+ workers. With so few union members these days, I can’t imagine that there would be any uptick moved by small stoppages.

Reagan gets a lot of flack in sociology courses for implementing antilabor neoliberal logics. But don’t sleep on the Carter administration. Notice that the decline starts in the 1970s.

Number of days “idle” due to work stoppages are, unsurprisingly, down too.

No evidence of re-invigoration. Just evidence of no more labor movement. Obviously, the decline of union membership is deeply connected to reduced union activity.

Obviously, we see that we’re in an era of low union membership and low union activity.

Counterevidence

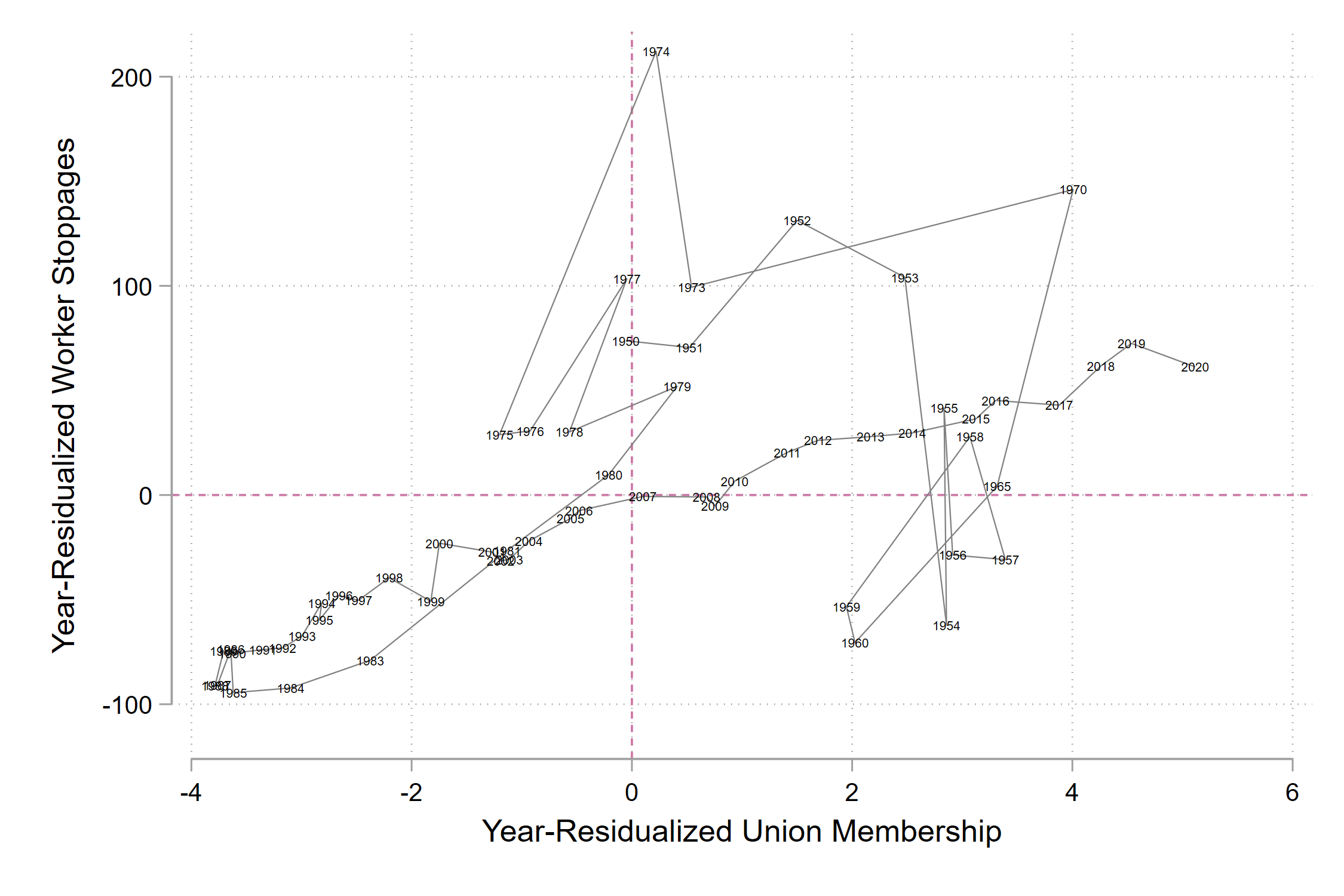

I’m mostly convinced that the labor movement is not reinvigorating. But here’s one possible piece of evidence against my pessimism. I estimated simple regression models predicting union membership with a linear year measure, and also estimated a simple linear regression model predicting work stoppages with a linear year measure. I computed residuals from each regression and plot them against each other. So we can see which years are relatively above or below the overall predicted line of demise.

You can see that years 2010-2020 are consistently “above” predicted linear trends of demise: There’s higher union membership rates than expected from 2010 onward based on a simple linear fit of decline, and higher rates of work stoppages in this period too. We can see the massive antilabor neoliberal era of 1980-2007 in the bottom left quadrant, where union power and numbers decelerated massively.

What if we went a little harder on ourselves and included a squared term for year? The decline isn’t linear, you know.

We still see the neoliberal antilabor era of 1980-2008ish play out in the bottom left quadrant (lower than expected union membership and work stoppages). We kind of see an unexpected rise of union power in the contemporary era, 2011 onward. We also see an era of big union membership without as much expected flaunting of clout (mid 1950s-mid 1960s), and era of big and active labor (1970s).

I’d overall say: maybe if you squint really hard you see unions not as dead today as you might expect. Turning to residualized trends we see a slight upward movement. But the absolute low levels of power and numbers is the biggest issue, in my opinion. And there, the US is very, very far away from a reinvigorated labor movement. Too bad. Unions are really good for ordinary and less powerful workers.

Median household income. Where we are, where we could have been

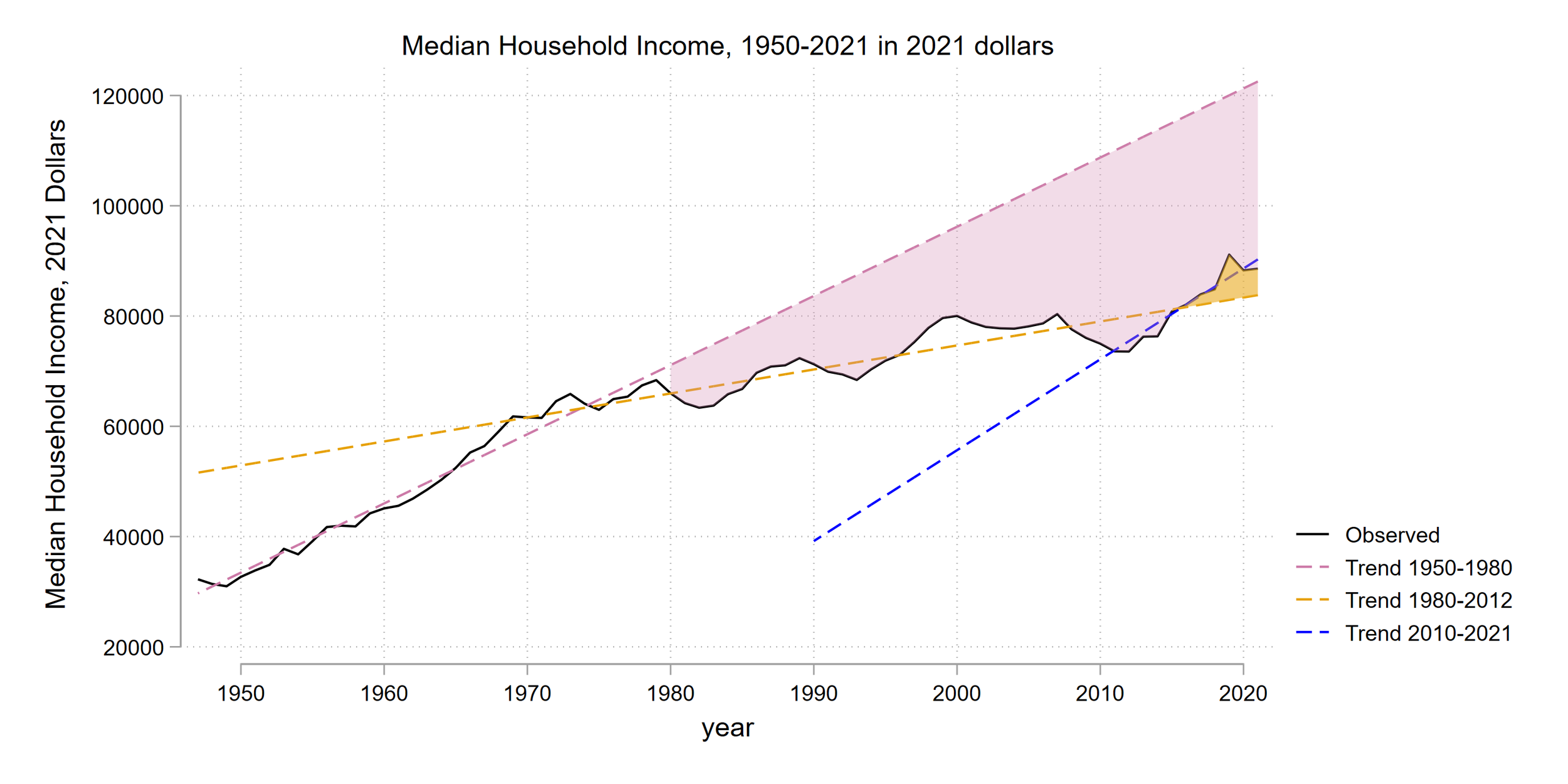

The census recently released data on median household income in 2021 (link downloads the excel file). For all families, it is $88,590. Not bad! Below I plot median household income in 2021 dollars from 1950 - 2021

Inflation adjusted median household income has gone up quite a lot, doubling since the mid 1950s. That’s pretty good!

But at the same time, it looks like we have three lost decades, the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Let’s look at the trends from median household income growth from three eras: 1950-1980, 1980-2010, and 2010-2021

If median household income had not stalled out in the early 1980s and continued on its 1950-1980 trend, we’d expect median household income to be around $120,000 today, not ~ $88,000.

The recent uptick of median household income growth beginning a bit after the Great Recession has gotten us slightly back on track to earlier times. But there hasn’t really been much time to catch up. If we stayed on the 1980-2010 stagnation route, we’d expect median household income to be around $86,000 instead of $88,000. A meaningful difference, but not totally earth shattering.

It’s a little easier to see the gap that the 3-decade stagnation produced if we fill in the space between trend and observed lines.

The last decade of revamped median household income growth has made up a lot of lost ground! But we’re still very much in the hole. So I guess how you feel about the recent trends reflect: 1] how much you focus on historical trends and counterfactuals 2] how much you privilege absolute changes 3] how confident you are that the trends from the last decade will continue into the future.

PS — Obviously projecting 1950-1980 growth into the next four decades is silly science fiction. The world is too complex and too many local, national, and global factors produced the stagnation. But it’s useful to think about, in my opinion.

I think Tyler Cowen's wrong about inequality

I’ve gone through a personal journey. I used to think, “Tyler Cowen’s employed at a nonsense Koch-funded center. That he’s taken seriously by anyone is a remarkable psyop.” I now appreciate his blog. His co-blogger Alex Tabarrok, although often a fool, did good work focusing on some of the shortcomings of the CDC and FDA during the pandemic. Some of the people in their orbit, like Zvi Mowshowitz, are good and rigorous thinkers. Tyler makes good book recommendations. His priorities are different than mine, and so it’s ended up being good to read him and think seriously about what he has to say. I’ve ended up thinking that perhaps he’s not entirely a shill but someone who’s reasonably serious and holds different values than myself.

But sometimes, he is just so wrong, in my opinion. And wrong in ways that are so obvious for a Koch-funded public-facing economist. It makes me wonder if all the book recommendations haven’t simply led me astray and my initial impulses were correct. I’m not there, but it keeps my journey in check.

I felt this way with his recent post, Wealth and income inequality have been falling, which links to his Bloomberg op-ed, Fight Poverty, Not Income Inequality.

In his op-ed, he states:

Wealth and income inequality have recently gone down in the US and other parts of the West, and the decline has been going on for the better part of the last decade. Yet it is not clear, to me at least, whether this is something to celebrate.

He links to a tweet by Matthew Yglesias as his evidence for declining inequality.

I don’t have much of an issue with this tweet or data source. The best study I’ve seen recently was Aeppli and Wilmer’s Rapid wage growth at the bottom has offset rising US inequality. From their study:

Yup, across a number of data sources, inequality has reversed / slowed / stalled from 2012 onward. But here’s where I start to disagree with Cowen. He says:

The recent decrease should come as no surprise. Markets are well below their late 2021 levels, and the wealthy hold a disproportionate share of the stock market. Executive compensation also tends to move with the markets, which affect the wealth of founders such as Mark Zuckerberg, who according to one measure has lost about three-quarters of his net wealth at its peak. And then there are all those former crypto billionaires, and not just Sam Bankman-Fried.

Umm, that’s not necessarily what’s causing the contemporary stalling / decline of inequality. Let’s look again.

We’re seeing 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles in the left column, and the ratios of these percentiles on the right. The decline of inequality has been due to the rise of low end earnings combined with a stagnation of middle earnings. The top, meanwhile, has continued to launch ahead of the rest. Put another way, top incomes separating from the middle has kept inequality levels from falling even further. I also don’t really buy the image Yglesias shows. That shows changes in the percent growth. But if we were to look at something like cumulative share of total income, we’d see something like this:

Not exactly the great reversal. Top is still separating from the rest, albeit at a perhaps slower pace. Cowen goes on.

I am not here to shed tears for the very wealthy or to argue that the bottom half doesn’t need more help. My question is this: Do we feel good about this state of affairs? I would merely observe that lesser wealth and income inequality have not brought new glories to the world.

I don’t know about this. Let’s look at total wealth distributions up to the pandemic, from the CBO.

Why am I showing this? Well, look at what happened during the Great Recession. The rich lost the largest chunk of wealth during the Great Recession, but (1) that’s because they held so much wealth and (2) it quickly rebounded. To say that the super wealthy like Zuckerberg have lost a lot of wealth in the immediate aftermath of a downturn is a pretty narrow viewpoint that probably won’t hold up, imo.

He argues that inequality critics are too radical.

But critics of inequality make a different and much stronger set of claims, saying that inequality is responsible for health problems, despair, bad governance and social unrest. Those arguments — focusing on inequality rather than the absolute level of poverty — are an essential part of the current critique of capitalism.

Why cite a 2006 book that makes these arguments seem old? Why not take a look at something concrete and recent, like Chetty’s work linking inequality, and inequality growth, to growing disparities of life expectancy?

“Why are all these radicals up in arms about a measly 12 years of extra life,” says someone who sounds pretty unreasonable.

What are the downsides of declining inequality?

Lower income inequality is not without downsides. Charitable giving is likely to fall. Fewer ambitious corporate projects will be undertaken. Major technology companies, which have seen some of the biggest declines in value, are laying off workers, most of whom will probably get lower-paying jobs and experience more anxiety.

Ooh, great! Cowen’s interested in charitable giving! I suspect he’ll be very interested in finding that labor unions are importance sources of charitable giving! Their decline contributed to growing inequality, so their contribution, plus the reduced need for charity to begin with with fewer folks living in precarious situations, should make up for the loss. Right!? Right? Cowen, why aren’t you returning my calls?

Also, if I didn’t know better, I’d argue that he’s cherry-picking issues. Like, couldn’t he also argue that extreme high levels of inequality are associated with stalled and diminished levels of economic growth? Wouldn’t that get Mercatus folks going? Hello? Cowen, are you there?

And it’s not as if people on the lower end of the income scale feel happier or more healthy because the wealthiest are now poorer. For most Americans, life goes on; their main economic concern is that high inflation will eat into potential wage gains.

Seems like a better decision to link to studies of inequality and happiness, for example this one, that shows that relative comparisons matter a lot for happiness. Why link to a Pew study of economic concerns? Weird.

It’s the unbalanced media attention that’s to blame.

For at least two decades, the attention given to rising income and wealth inequality was huge, among both policymakers and academics. Over the last decade, the attention given to falling income and wealth inequality has been tiny. Our views of this issue, shaped by the media, may be seriously out of date.

Or, that we’re starting from an absurdly high stock, at near maximum levels of wealth inequality. Or, that few probably believe we’re in the middle of a great wealth transition anytime soon.

His conclusion:

Maybe inequality wasn’t the problem in the first place. That’s why I’m not cheering at its decline, and why I suspect not everyone else is, either. The real challenge isn’t how to reduce the difference in wealth between the rich and the poor. It’s how to reduce poverty.

I disagree. The era of massive inequality growth has fundamentally changed the nature of growth. Less for the bottom when the top soaks most of it up.

I disagree. Earnings and poverty are necessarily relational. The top separating from the rest can really distort the whole economy. Read a bit of Robert Frank.

Conclusion. Weird. Totally off. And in ways totally predictable from somebody in his institutional position.

It’s a good reminder that underneath the nice book recommendation and classical music discussion and cute over/under-rated questions and mentions of Strauss is a big old pile of Koch money, which does a lot of selection on the arguments. I still like him, but this was a good reminder of why I can’t really take him too seriously.

Individualism and Collectivism: The “Greater Good” is sometimes “My Good is Greater”

Imagine the following. There’s a terrible war going on, and you’re fighting on the side of rightness and justice. You’re in the army and everyone in the army is in favor of winning the war, winning it quickly, winning it completely, and winning it while minimizing the amount of death and devastation that wars naturally bring. Think of the following scenarios:

The general surveys a map. There’s a high risk, high reward attack to be made in a dangerous area. “If we can win this battle, the path into the enemy’s capitol is all but assured. It’s heavily fortified and our prospects for victory are slim. But if we succeed, the war will end quickly and countless lives will be saved.” The general decides the risk is worth it and orders the attack.

The lieutenant colonel reviews the plans for this foolhardy attack. “Has the general lost his mind? This attack is hopeless. We’re lambs going into the slaughter. He’s completely ignorant of the reality on the ground. How can I justify sending my best men into certain death? This will make us all the weaker after this attack assuredly fails. We’ll lose the line, try to fall back, and we’ll all die.” The lieutenant colonel sends in the troops, but reserves his best platoons to the back to prepare for the inevitable retreat.

On the front line the soldiers are bombarded with bombs and bullets. The lieutenant leading the front line platoons yells to his soldiers to hold the line. “Why the hell are we here?” he thinks to himself. “This is hopeless!”

Deserters from both sides watch bombs explode in the distance. “What fools they all are,” one says. “If every man decided to stop fighting, the war would end.”

Here’s a rough sketch of what each person might be thinking:

The general thinks, “The brave soldiers on the front line must make a sacrifice for the common good to end the war quickly.”

The lieutenant colonel thinks: “The lousy general needs to sacrifice his lust for individual accolades and not make such foolhardy swings for glory. I will fortify the retreat so we can fight another day and win this just war.”

The lieutenant thinks: “The greedy lieutenant colonel musn’t hoard our strongest fighters for his personal protection on a retreat. If we’re going to fight we must be all in.” The lieutenant also yells: “Hold the line! Don’t let the enemy break ranks to kill your brothers behind you!”

The deserters think: “Those fools with their lust for glory, their fear of maintaining good standing among their peers. If only they’d risk for the common good, war would be a thing of the past.”

Hokey. Do you see why I’m not a famous novelist? But this line of decision-making isn’t the most out there, right? Which of these folks are operating with a logic of individualism? Which are operating with a logic of collectivism? I’d say all are doing both and neither and both. I’d say the general has a reasonable viewpoint towards collectivism. I’d say the deserters do too. I’d say the deserters are unrealistic if they think all soldiers can drop their rifles at the same moment for the common good. I’d say anyone thinking that leaders aren’t motivated by personal incentives and glories are full of it. I’d say people caught in the middle of a chain of command and authority face criticisms of faulty collectivism and faulty individualism from all angles, accurately. I’d also say a war with an obvious good and bad side presents one of the simplest and most straightforward social contexts to differentiate individualism versus collectivism.

The point is that there is not a single expression of individualism, nor a single expression or form of collectivism, communalism, pitching in for the common good. A world with multiple institutions, priorities, identities, networks, and values is not a world with clean lines between individualism and collectivism. But you wouldn’t know that if you only read prominent media pieces on the coronavirus.

Covid Talkers and Simple Ideas

Being a public facing talker / thought leader about the pandemic must be really hard, especially if you are a journalist, academic, or scientist. You need to make a convincing case while doing your best to remain (or appear to remain) as unbiased as one reasonably can be expected to remain. My hot take: I think everyone has actually done a really good job, considering the circumstances, including public facing talkers / thought leaders. But every now and then I see people talk about “doing one’s part"/pitching in/common good versus individualism/selfishness/you’re-on-your-own, and it feels so deeply nonsensical and superficial. It feels like someone is trying to cram real life complications into Disney character tropes of simple and cleanly divisible good and bad.

Take Katherine Wu’s recent article in the Atlantic, “The Biden Administration Killed America’s Collective Pandemic Approach.” Here are a few representative quotes:

“The onus of public-health measures has really shifted away from public and toward vulnerable individuals,” Ramnath Subbaraman, an infectious-disease physician and epidemiologist at Tufts University, told me

Here’s another:

“It is public health’s job to protect everybody, not just those people who are vaccinated, not just those people who are healthy,” says Theresa Chapple-McGruder, the director of the Department of Public Health in Oak Park, Illinois…Throughout the pandemic, American leaders have given individuals more responsibility for keeping themselves safe than might be ideal; these revised guidelines codify that approach more openly than ever before. Each of us has yet again been tasked with controlling our own version of the pandemic, on our own terms.

(I actually like Chapple-McGruder’s point!). Wu later describes the public health model of behavior:

A medical framework—almost resembling a prescription model—is not public-health guidance, which centers community-level benefits achieved through community-level action. People act in the collective interest, a tactic that benefits everyone, not just themselves.

As I’ve sat on this draft, Wu has written another article about fall boosters. Again, the downsides of individualism are centered:

The reality that most Americans are living in simply doesn’t square with an urgent call for boosts—which speaks to the “increasing incoherence in our response,” Sosin told me. The nation’s leaders have vanished mask mandates and quarantine recommendations, and shortened isolation stints; they’ve given up on telling schools, universities, and offices to test regularly. People have been repeatedly told not to fear the virus or its potentially lethal threat. And yet the biggest sell for vaccines has somehow become an individualistic, hyper-medicalized call to action—another opportunity to slash one’s chances at severe disease and death. The U.S. needs people to take this vaccine because it has nothing else. But its residents are unlikely to take it, because they’re not doing anything else.

Here’s Gregg Gonsalves, one of the most online public health people, writing in The Nation:

There is a decadence to the Democratic embrace of rugged American individualism, where we owe each other nothing, that’s almost, well, Republican in spirit. Personal risk. Personal choices. Personal responsibility. Paul Ryan—remember him?—would be proud. The Gridiron Dinner was just American Covid-19 policy personified: no precautions beyond vaccination and Paxlovid for the unfortunate few who catch SARS-CoV-2.

Except that this is policy for the privileged, who are boosted (probably twice by now—and, full admission, I am doubly boosted myself) and know just whom to call to ensure they get the best medical care should they get sick. But, as Harvard emergency physician Jeremy Faust just wrote, this notion that we can calculate our own personal risk is a chimera: “Nobody has a good handle on what their individual risks truly are. How could they?… the math is remarkably complicated. We can’t expect people, even experts, to do this on the daily. That makes the ‘leave it all up to individuals’ approach pretty unworkable at the moment.”

Furthermore, as Aparna Nair, a historian of public health, told Ed Yong at The Atlantic last year, “Framing one’s health as a matter of personal choice ‘is fundamentally against the very notion of public health.’”

If I don’t think about it too much, these kinds of arguments make total sense. Yes, let’s all pitch in for the common good! How could anyone be reasonably against that!? But if I think about it for more than a hot second, the complexity becomes much more understandable.

The simplest response is that we haven’t all been in this together. At least not after the first few weeks. Here are a few very basic points to back up this claim.

Earlier, I hashed out an at-most 30% true theory of red state turmoil of professors returning to the classroom. There’s a big socioeconomic gradient of who could work from home during the pandemic.

My students at UMN are very aware of the disparities of in-person work versus laptop work. Many of my students were on the front lines in the pandemic. I’d describe their view of the “laptop class” as, at best, mixed. They haven’t exactly seen the “Stay Home, Stay Safe” crowd as working towards the common good.

In the Twin Cities during the vast majority of the pandemic, private schools were open, in person, and thriving. Public schools were shut down with the thin facade of google hangouts substituting for education.

I will just note: I have yet to meet a parent in the Public Health crowd that has not supplemented their own “Stay Home, Stay Safe” with some optional network node to advance their child’s well-being, whether this be private school, tutoring, or supplemental childcare. So the lived reality proved to be more complex with wider bars of acceptable risk tolerance than official messaging.

A silly anecdote I just keep thinking about. On a run in mid-day mid-fall 2021 semester. I live near mansions in St. Paul. I ran by one that had a well established sign on lawn, “Stay Home, Stay Safe.” I ran by this house frequently and saw the same car parked out front. This time I saw the Hispanic couple bringing their cleaning supplies inside. Their tween daughter in the back of the car on an ipad (this was during the school day during the school year, but public schools were shuttered and online.).

Say what you want about pandemic decisions of social distancing, masking, etc. (I distanced, masked, vacc’d, boosted, etc., by the way. Don’t mistake me for someone who’s going to try and convince you that Melinda Gates put an ancient Soviet uranium chip in the Moderna vaccine). The big point: has the US population ever undergone such a mass change of personal behavior for the greater good? I’d say we’re at least on par with victory gardens. That shouldn’t be hand waved away. But the communal effort championed by Wu and her sources, Gonsalves, etc., were not fully communal. I’d argue that the benefits and costs of our collective no pharmaceutical interventions were widely distributed across social strata in, dare I say, very unsurprising ways.

Which is to say: these ideas of individualism and communalism must coexist with existing systems, existing power relationships, existing norms, existing practicalities, and existing incentives. Society isn’t one thing. It’s complex. Individualism for the general means something different than individualism for the deserter. And the tradeoffs for the greater good as ascertained by the general may or may not make sense to the lieutenant. Such must be the case when making a general claim about a third of a billion people living across a vast system of social environments.

Before I go further on why I think the individualism discussion has been superficial, let me lift out two other pseudo-related examples.

Schools

Look at the last quoted Wu article. She bemoans the lack of testing at schools. But testing at school was highly consequential, resulting in a lot of chaos, uncertainty, and routine-disruption. Different countries made different decisions (Denmark made very different decisions regarding schools compared to the US, for example). I don’t want to go too far into the deep end of the pool, but a few things are obvious now. 1. There has been a massive amount of learning loss among children. 2. It has been highly, highly unequally distributed in the most unsurprising of ways. 3. Private schools reopened and got onto the normal track much more quickly and aggressively than public schools. And there’s an ever-so-slight correlation between socioeconomic status and private school attendance.

I’m not going to link. But there’s a prominent academic who’s very much in the education / kids / covid world. I’d guess they’re in the top 95th percentile of fear-of-covid. They recently (as of the first drafting of this post, six months ago) were very angry that their school dropped its mask requirement. This person bemoaned that their child wore a kn95 mask, but that these weren’t universally required to wear. That masking is a collective endeavor, not an individual one, that it works when we all do our part. Their kid got covid (the kid’s fine, btw) and had to miss some in person recreational activities. Side bar: this person has been located in some of the most extremely prestigious institutions for over two decades. They’re probably in the top 5% of the household income distribution. Their kid survived without incident. Their school is very high quality and comprised mostly of high SES children of academics.

I’d ask: who should absorb the brunt of collectivism? Because what I’ve seen is that primarily poor and minority students have suffered extraordinarily because of school shutdowns and disruptions. Open up any recent study and you’ll see American-style school closure and disruption has been a nightmare for poor and Black students, while more privileged and White students have largely recovered. This method of collectivism didn’t happen in many affluent countries. Is maintaining normal school “individualism,” “selfish,” “harmful,” etc., or would catering to elite preferences of zero covid in fact be the “individualized,” “selfish,” and “harmful” decision, insofar as the resourced have an easier time compensating for low functioning school systems? There’s not one individualism. There’s not one collectivism. Your communitarism is my getting trampled on. Your greater good may in fact be a claim about whose good is greater. It’s not easy. It’s multileveled and complex. That’s so obvious to me and should be for anyone who’s ever taken a halfway decent social science course.

(Sidebar: I realize masking is not the same as shutting down schools. But I’d argue that, at minimum, masking children should be thought of as a highly disruptive decision without an overwhelmingly obvious set of communal benefits.)

Masks on planes en route to fun

I’ve flown twice in the past three years. Each time masked the whole time (update: I didn’t mask the whole time on an August flight, four months after first drafting this). Whatever. I’m the laptop class so this wasn’t too inconvenient for me. I monitor the substack “Your Local Epidemiologist,” because it represents in my mind the maximum combination of intelligence/thoughtfulness and covid fear/pro-restriction viewpoints, both by the very intelligent author and her very intelligent commenting community (not to be too obvious, but I have a very high level of respect for this blog). Following the dropping of masking requirements on planes, YLE discussed the various issues of plane transmission. Before moving forward, I thought she was intelligent, thoughtful, and reasonable in her discussion. But one highly ranked comment kept rattling in my head:

Here’s one way to interpret this comment in terms of individualism versus communalism (I’m also loosely using this as a stand in for the comment section of the substack): we did our part to stay safe on the plane, protecting ourselves and others with our N95s. Yay! If only a policy were maintained so that everyone pitched in to do their fair share. That’s a frame of these medical students contributing to the collective good, and non mask wearers focusing on individualism.

Here’s another: privileged medical students want to fly to an optional footrace, the entire chain necessitating low paid and low authority workers to be in risky in person situations for the entire day. There’s no way in hell they correctly wore their N95 masks in every space between leaving their house and re-entering their house. I’ve been on planes. Everyone has Coca-Cola time. Or maybe they moved it down every so quickly to take a sip of water. But the point: isn’t the choice to fly to an optional recreational event in a pandemic, necessitating a whole slew of workers to remain in person for long stretches of time to cater to these whims, not a profoundly selfish, even individualistic, choice? Wouldn’t pitching in to the collective good mean not flying to the Boston marathon? That is as reasonable a story as the first, in my opinion. Now, don’t get me wrong: great job running the Boston marathon! Get it! just don’t delude yourself with a narrow definition of collective effort and individualism.

Here’s a third way to interpret it. According to this Pew poll, most Americans don’t fly in a year. 75% of Americans fly less than twice a year. Airline masking received a lot of oxygen, not only in major news sources and academic twitter, but among public health folks as well. How is this focus not another example of public health / academic chatter getting distracted by palace intrigue among the well to do?

My Point

Individualism is way more complex of a concept than the public health oriented commentators suggest. Individualism is a web of related concepts that exist within a broader society with many intersecting social positions and institutions, and which pushes in directions of both solidarity and atomization. Individualism and communalism coexist with organizations, which themselves have incentives and values, and which are connected and/or atomized. Individualism and communalism themselves are situated within power relationships that enable social closure, opportunity hoarding, and claims over material or symbolic resources. There never has been, and never will be, simple and universally applicable definitions of individualism and communalism outside of Disney movies.

And contra Wu, Gonsalves, Yong, etc., the disparities of communal activity were not due to libertarian boogeymen, but because individualism and collectivism are complex topics that likely made sense in local contexts. I think a lot of folks just didn’t think too seriously about diverse and broad systems, identities, tradeoffs, and incentives that existed during the pandemic.

I’m reminded of a good critique of libertarianism: a libertarian policy fails and the libertarian says, “It failed because people kept interfering with the market with their pesky society and norms and communities. If only we got a purer market, my ideas would have been shown to be true.” But, of course, markets are social things and cannot be fully isolated from broader society. I now see the same foolhardy logic among the most online public health folks: “If only we communal’d harder without that wretched individualism. Then we wouldn’t have ever had covid.”

It’s complex. I’ve started discounting the value of arguments made by folks who lean too much on simplistic ideas of individualism and/or collectivism. It’s a shame that public-facing public health folks use such arguments, as they cover up much of the very real and important complexity and series of tradeoffs we faced during the pandemic.

We probably shouldn’t downplay learning loss

I try and keep a level head when discussing social problems, but the hardships that young adults and children faced during the pandemic really riles me up. Here in the Twin Cities, the negative consequences of shutting down public schools became pretty obvious pretty quickly. Why did I bold public? Because as far as I can tell, private schools opened back up much more quickly. Here’s the best data I’ve seen at the national level, collected by the NCES:

This aligns with what I saw on the ground here in the Twin Cities. And qualitatively, in person schooling went just fine, while online schooling, especially for young people, was a disaster. Hey, does anyone want to guess whether these kinds of trends might translate into things like, I don’t know, massive inequality?

To very little surprise, yes, it turns out that the last two years have been an inequality production machine unlike anything we’ve really seen in recent generations. For example, see this New York Times article on learning loss.

The three big points, in my opinion.

National test results released on Thursday showed in stark terms the pandemic’s devastating effects on American schoolchildren, with the performance of 9-year-olds in math and reading dropping to the levels from two decades ago.

and

The declines spanned almost all races and income levels and were markedly worse for the lowest-performing students. While top performers in the 90th percentile showed a modest drop — three points in math — students in the bottom 10th percentile dropped by 12 points in math, four times the impact.

and

In math, Black students lost 13 points, compared with five points among white students, widening the gap between the two groups. Research has documented the profound effect school closures had on low-income students and on Black and Hispanic students, in part because their schools were more likely to continue remote learning for longer periods of time.

Why might this matter?

“Student test scores, even starting in first, second and third grade, are really quite predictive of their success later in school, and their educational trajectories overall,” said Susanna Loeb, the director of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University, which focuses on education inequality.

“The biggest reason to be concerned is the lower achievement of the lower-achieving kids,” she added. Being so far behind, she said, could lead to disengagement in school, making it less likely that they graduate from high school or attend college.

But this is probably just some silly MTurk study or low quality survey, right?

The National Assessment of Educational Progress is considered a gold standard in testing. Unlike state tests, it is standardized across the country, has remained consistent over time and makes no attempt to hold individual schools accountable for results, which experts believe makes it more reliable.

I was surprised that the New York Times didn’t have a spiffy visualization of the trends, given how many of their other articles include such things. In fact, the NYT didn’t even link to the report! Luckily, the Washington Post did, and Alec MacGillis selected some nice summary measures of the decline.

Here is one:

Massive declines in reading and math scores. Decades of real progress wiped away in a few short years.

Unsurprisingly, these reversals did not occur uniformly across the population. You can see that groups differed in the decline.

You can see striking racial gaps, particularly among math scores. Black students saw a 13 point decline, Hispanic 9, and White and Asian around 6.

The pandemic didn’t produce learning loss equally. We can look at the top and bottom percentiles of test scores to see more spread of educational outcomes. Below’s a visualization of the spread growing, from a nice explainer thread:

Loss at the bottom, stability at the top. More education inequality after the pandemic than before. But this doesn’t really do justice to the profound shift of educational inequality that has occurred. Below is a table of the gap between high and low test scores from the NAEP.

Here we see 9 year old math test scores at the 90th (high scores) and 10th (low scores) percentiles. The 90ths percentile was not hit particularly hard, staying at around the 280s. But the low scores dropped to 1986 levels, producing a spread that' hasn’t seen seen in the past half century. And by the way, the last had century has had itself a fair amount of educational inequality.

The production of more inequality along established tracks was also found by Raj Chetty in his Economic Tracker. Below is the relative change in math scores among high, middle, and low income schools.

These are relative changes to the baseline. And the baseline had, unsurprisingly, significant gaps in performance across high-, middle-, and low-income schools. So The already existing SES gaps were exacerbated in the pandemic.

On the ground reports seem to show that students are really struggling. A quote from a recent New York Times article about New York City students:

Data on how New York City students are faring academically has been scarce. The state has not yet released the last school year’s test results, and the city has not made public data on how students performed on tests it administered during the school year.

But a survey of more than 100 New York City teachers found that the vast majority believe students are behind academically compared with how they fared before the pandemic. And national test results released Sept. 1 found that 9-year-olds fell far behind students who took the test in years past.

“What I’ve seen is astonishing,” said Aaron Worley, a social worker at P.S. 243 and P.S. 262 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. “Kids in fifth grade that are struggling with their reading, their writing, their sentence comprehension — it’s alarming.”

The schools chancellor, David C. Banks, joined the mayor on Thursday at P.S. 161, the site of one of the city’s new dyslexia programs. He described the issue as a central piece of a larger challenge: “the fundamental way in which we teach our kids how to read.”

A quote from a story from the Los Angeles Times on LA students:

A Unified test scores released Friday showed the harsh reality of the pandemic’s effects on learning across all grade levels, with about 72% of students not meeting state standards in math and about 58% not meeting standards in English, deep setbacks for a majority of Los Angeles schoolchildren who were already far behind.

The scores show that about five years of gradual academic progress in the nation’s second-largest school district have been reversed, L.A. schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho said Friday.

“The pandemic deeply impacted the performance of our students,” said Carvalho, who spoke at a news conference at Aragon Avenue Elementary School in Cypress Park. “Particularly kids who were at risk, in a fragile condition, prior to the pandemic, as we expected, were the ones who have lost the most ground.”

and

The types of students who fared the worst “are not small subgroups in California, particularly in L.A.,” said UCLA education professor Tyrone Howard. “This has consequences for us as a state, as a city [and] I think it poses significant challenges about who we are and who we want to be if we’re not intentional about who is being left behind.”

I’m not sure if this equals the tragedy of the pandemic, but it sure seems close. A stunning disaster that fell on the most marginalized and least powerful members of our society: poor and minority children. In my humble opinion, anybody who professes to care about equality, justice, or fairness should be feeling their blood boiling right about now.

The above is the outcome of closing schools, closing public schools more than private ones, and keeping them closed for a very long time. I haven’t linked to any study for this claim because, well, it’s so obvious that I don’t think we need a study on it. But school closure and all the school disruption that has occurred in the last two years is such the obvious reason why this happened. Really, any parent or young person could probably let you know that online school was, well, not exactly the optimal route, particularly for students from more difficult social origins.

Prominent Academics React Surprisingly

One might think: “prominent sociologists on twitter are big into education, race, and disparities. I bet this is a big deal to them!” That’s what I thought. But the reactions to these learning loss findings have been pretty surprising. Below are examples from very prominent academics who focus on education, race, and inequality:

Here’s one example:

Here’s another:

Here’s another:

Responses have been much hand-wavy-er than I would have anticipated. The responses above have very 80’s guy execu-speak vibes that I don’t think rise to the occasion that we’re in.

In the interest of being constructive, I’d like to call on academics to take the issue of learning loss a tad more seriously. I’d ask folks to think of this as a generational disaster in terms of its production of educational inequality. I think there are a few things people should keep in mind if they’ve been reacting in the kinds of ways shown above.

It might be shortsighted and overly postmodern to question these findings.

The learning loss findings seem to be rooted in pretty mainstream and straightforward metrics of education. I’d argue that denying learning loss may be a pretty postmodern stance that can be easily mobilized to logically argue for the dismantling of public education and the Department of Education. If this stuff isn’t real and measurable, why throw money at such a non-thing as learning?

If you think test scores are too rigid and the squishy side of education is more important, I’d argue the squishier part of education was worse during the pandemic (anyone else sitting in online kindergarten would surely agree, and feel free to email me if you want some concrete examples).

There’s no reason to try and provide cover for the United States’ decisions.

That there might be some massive unanticipated outcome of a radical, experimental, and ad hoc policy choice seems…pretty obvious. There’s little need to try and deny it. One could argue that the entire discipline of history is the study of a cascade of unintended consequences.

Perhaps you’d argue that no other outcome was possible. I’d ask you to think long and hard about the implications of such an argument.

Learning loss looks to be very, very consequential for justice and equality.

I’ll admit that I haven’t read his book closely, but wouldn’t school shutdowns be defined as racist in a Kendi-style framework? The race and class gaps are just so massive. I’d argue that it does little good to try and downplay a massive production of inequality.

Perhaps you might argue that the costs were worth it. But I’d ask that you think very seriously about this argument.

The production of generational inequality is not ok, even in hard times.

Public education expansion occurred during the following events: the Great Depression, World War 2, the Vietnam War, Civil Rights, 9/11, the opioid epidemic. Which is to say: history is littered with hardship, either at the macro or local levels. We won’t reach history’s end, so educational attainment will arguably always occur in difficult times. I’d argue that hardship is not a reasonable explanation or excuse for producing a generational-level of education inequality. Or…if it is, then we necessarily must shut off educational equality as a goal or possibility, since there’s no reason to think we’ll be able to successfully avoid hardship for a sufficiently long enough time to close educational gaps.

There were other options playing out at the time.

European countries provided many different sets of decisions, including opening schools much earlier and restricting masks to older children and adults. One of the people I mention wrote a prominent article in the New York Times titled something like, “European countries have the welfare state. America has women.” So academics definitely have the wherewithal to compare policy decisions across social contexts. We might not like what we did, or we might think that it was worth it, but…this was at least partially the outcome of a decision made from a broader suite of choices.

Denying or downplaying learning loss undermines your legitimacy.

I’m a little worried that academics are operating like PR officers providing cover for a company’s massive oil spill. The learning loss experienced during the pandemic is very obvious in the data. It’s obvious in it importance. I suspect that folks are equivocating because school closure was primarily energized by the left side of the political left. I realize this makes the outcomes of school closure embarrassing, but denial, or omission, or equivocation of the issue simply calls into question one’s broader legitimacy and trustworthiness.

We probably won’t reverse these inequalities.

I’d recommend settling into the mess we’re in. Or at least, I’d strongly consider that these gaps and depths of learning loss will not be easily, or broadly, made up. In September 2020, Alec MacGillis wrote a great ProPublica / New Yorker article. I recommend reading it. He cites research showing that kids have real difficulty making up learning loss following things like natural disasters.

There will be new kinds of inequalities that exist between generations.

Kids going through school right now will be disadvantaged compared to those who came before and those being born right now. I have no idea what this means for social policy, employment opportunities, the distribution of social welfare, or issues of mobility and status attainment. But I suspect it’s going to be weird. It seems reasonable to anticipate a whole bunch of odd social problems and inequality coming down the pipe.

One might suggest that social policies should begin to be designed to assist today’s children.

There are going to be very serious consequences carried forward by millions of children.

Sometimes I’ve seen people say, “It’s ok because everyone lost a year.” Or whatever. But that’s not the case. When we look at the data, we see that Black, Hispanic, Native American, and poor children fared the worst. Remember the public/private split that began this post. School closures and the resulting learning loss could be argued to be the most consequential intergenerational inequality change of our lifetimes. It could be argued as the most consequential amplifier of racial inequality of our lifetime (or at least, it could rival mass incarceration).

I suspect that the consequences of producing race and class inequalities on steroids will be very predictable. I can think of few reasons to deny, justify, or hand wave these issues.

I don’t think we can just shut up or ad hoc our way out of this. There are snowball risks.

I’d be shocked if consequences didn’t continue to snowball. For example: public school enrollment has been seriously hit. Here’s an example from Minnesota:

May not look huge, but I’m seeing similar 3-7% declines in enrollment in reports from different cities and suburbs. Enrollment declines of these kinds of magnitudes have massive implications for public school funding. For example, an article from the New York Times a few months ago:

ORANGE COUNTY, Calif. — In New York City, the nation’s largest school district has lost some 50,000 students over the past two years. In Michigan, enrollment remains more than 50,000 below prepandemic levels from big cities to the rural Upper Peninsula.

In the suburbs of Orange County, Calif., where families have moved for generations to be part of the public school system, enrollment slid for the second consecutive year; statewide, more than a quarter-million public school students have dropped from California’s rolls since 2019.

And since school funding is tied to enrollment, cities that have lost many students — including Denver, Albuquerque and Oakland — are now considering combining classrooms, laying off teachers or shutting down entire schools.

All together, America’s public schools have lost at least 1.2 million students since 2020, according to a recently published national survey. State enrollment figures show no sign of a rebound to the previous national levels any time soon.

So…going forward we’ll have kids with more needs and we’ll have fewer resources to handle them. We’ll see lower funding for public schools with more resourced kids in private, charter, and homeschool systems. That might well be a new force of more and more serious inequality. That doesn’t seem like something that can be easily ignored or discounted.

So maybe we could just, like, recognize this to be a big deal?

Maybe I’m misreading the scene. But I’d like to use this space as a call to maybe pay a bit of attention to the learning loss that was created by school closure. I’d like to gently push back against academics who are downplaying these findings. I realize it’s embarrassing when one’s “side” creates a disaster. But the stakes are too high to ignore the issue. I’m increasingly convinced that we’re facing a once-in-a-century social problem that holds the potential to snowball into something truly awful. We really can’t afford to downplay it.

Flood the zone with productivity

I’ve now re-read Katy Milkman’s How to Change: The Science of Getting from Where You Are to Where You Want to Be. For all the pop-ish productivity books, I’d say this is one of the better ones. If you don’t intend to read it, I think this Goodreads review sums up the main points pretty, if too, succinctly.

Compared to other books that have variations on titles like, “How to Change: The Science of <>”, Milkman tends to be more thoughtful and conditional in her advice. Lots of underscoring that contexts and situations vary, lots of emphasis that one-size-fits-all solutions often don’t exist. You see in Point 3: Milkman says that gamification matters, but spends just about as much time highlighting the limitations and unanticipated downsides of not getting a “magic circle” fixed (e.g. buying into the game). So…lots of good stuff.

So here’s where I’m at right now: there are lots of great habit / productivity books out there. And the advice is almost always reasonable, doable, and rooted in empirical findings. But…they almost never work for me. I’ve been thinking about why. And here’s a hokey theory: what if productivity people are with one hand giving you advice that, in a social vacuum, is good, but with the other are flooding the zone with proverbial shit?

I thought of this as I read Gerd Gigerenzer’s How to Stay Smart in a Smart World. That book’s, ok. You don’t want to go into it hoping to glean cutting edge information about artificial intelligence. Rather, Gigerenzer shifts focus onto people living in a world with an often confusing and contradictory set of facts: artificial intelligence is extremely powerful and amazing, and artificial intelligence is super over-hyped. It’s also cut with a set of cranky older gentleman arguments about big tech which I enjoy.

Anyways. Gigerenzer at one point talks about the various nudge / behavioral economics / “How to Change” social manipulation/influence techniques that tech companies study and deploy to keep you online. One example is Snapchat, an instant messaging service, using little fire pictures to signify streaks of days that you communicate with particular friends. I don’t use snapchat, but I googled this, and apparently it looks something like this.

Hey! That looks a lot like Milkman’s Point #8! Milkman also discussed using things like “Memory Palaces” or acronyms to remember things (Please Excuse my Dear Aunt Sally, e.g.). This being compliance season, I have about 46 decks of training slides to prove to the University of Minnesota that I am an ethical and professional employee. Which means that I’ll soon be exposed to roughly 120-140 easy to remember simple acronyms to remember the key points: Remember TRG (trust, routine, grow), 123 (One mention, report TO a THIRD party), etc. Acronyms really stop working when you’re exposed to lots of them, right? Even when it’s important information, like, what to do as a professional with responsibilities at work. And if you look around the materials produced by big companies / institutions / etc., they sure look a lot like “How to Change” lessons.

And that got me thinking more: what exactly are the day jobs of the “How to Change” “How to be Productive” “The Science of Microbehavior” set? Well, Milkman’s a fellow professor! She teaches in the prestigious business school at the University of Pennsylvania. Here is a sample of the courses she teaches.

Impressive! And the thing to realize about UPenn: it’s an Ivy League school that really advertises the high octane professional career people tend to connect to after graduation.

As far as I can tell, a large chunk of the “How to Change” set are in very similar teaching arrangements. Which seems to suggest that lots of future business / managerial / advertising / finance / etc. folks are steeped in “How to Change” empirical social sciences. Which would make sense why Snapchat has a streak fire emoji. And if you look around, you’ll see that lots of the “How to Change” type tactics / nudge tactics / etc. are everywhere.

Which…kind of feels like flooding the zone with shit, to quote Steve Bannon:

“The Democrats don’t matter,” Bannon reportedly said in 2018. “The real opposition is the media. And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.”

This idea isn’t new, but Bannon articulated it about as well as anyone can. The press ideally should sift fact from fiction and give the public the information it needs to make enlightened political choices. If you short-circuit that process by saturating the ecosystem with misinformation and overwhelm the media’s ability to mediate, then you can disrupt the democratic process.

Bare knuckled! Bannon’s key insight: a political candidate can fundamentally change the nature of their relationship to the media if they constantly produce nonsense, bloviation, and bullshit. Or: Romney erred by only producing a small number of gaffs (big bird, takers, binders of women) and responding by trying to correct. He should instead have produced even more gaffes! Or, to riff on Stalin: One gaffe is a trajedy. Millions of gaffes are a statistic.

It kind of feels like “How to Change” tactics are supported through teaching hundreds upon hundreds of MBA students the empirics of how to change person behavior. These MBA students then enter influential positions of wide reaching companies. They then use at least some of their behavioral economics / behavior change insights in ways that eventually get translated into unremarkable Joe’s like me getting inundated with games, acronyms, streaks, etc. Which…makes these tactics feel kind of gross and business-y (for lack of a better word) and difficult to differentiate from the broader tech/business/pr/hr/advertising world that relies heavily these days on behavioral economics. Which, kind of undermines the ability to apply these lessons to my daily life (not biting my nails is just another streak, PEMDAS sits alongside the 120 compliance acronyms I’m now supposed to remember).

Which is to say: I wonder if behavioral economists / “How to Change” folks have flooded the zone with their proverbial shit, which, now that it’s been broadly implemented and scaled, changes the nature of an unremarkable person like me to these tactics, perhaps ultimately undermining the effectiveness of these tactics. Just a thought.

Wordsum isn't IQ. I don't think we're getting dumber.

Scott Alexander at Astralstarcodex just posted his monthly dump of website links. These are always a grand hoot. The below caught my attention:

The GSS doesn’t have an IQ test. What is has is the “wordsum” item, which is basically a vocabulary test. Here’s how the GSS describe’s the item:

“We would like to know something about how people go about guessing words they do not know. On this card are listed some words--you may know some of them, and you may not know quite a few of them. On each line the first word is in capital letters -- like BEAST. Then there are five other words. Tell me the number of the word that comes closest to the meaning of the word in capital letters. For example, if the word in capital letters is BEAST, you would say "4" since "animal" come closer to BEAST than any of the other words. If you wish, I will read the words to you. These words are difficult for almost everyone -- just give me your best guess if you are not sure of the answer. CIRCLE ONE CODE NUMBER FOR EACH ITEM BELOW.”

Here’s an example of what the items look like.

Here’s a nice paper on the topic. Seems like wordsum has been used to refer to constructs such as: verbal ability, intelligence, vocabulary, cognitive sophistication, knowledge of standard English words, linguistic complexity, and knowledge and receptivity to knowledge.

So maybe this measures a person’s general intelligence. Or maybe it measures a person’s verbal complexity, vocabulary, knowledge of standard English, etc.

Also … hasn’t IQ increased pretty significantly across cohorts, via the Flynn effect? So why are we seeing the opposite here?

I was under the impression that IQ stayed relatively constant, or maybe declined a bit, as you age. I did some very shoddy googling and found a not-so-sketchy website that had the following figure:

So fluid intelligence, things like reasoning skills, decline with age, and crystalized intelligence, like…knowledge of words…increases over age? (I’m glad the declining fluid intelligence doesn’t apply to 30-something sociology professors. That’d be dreadful).

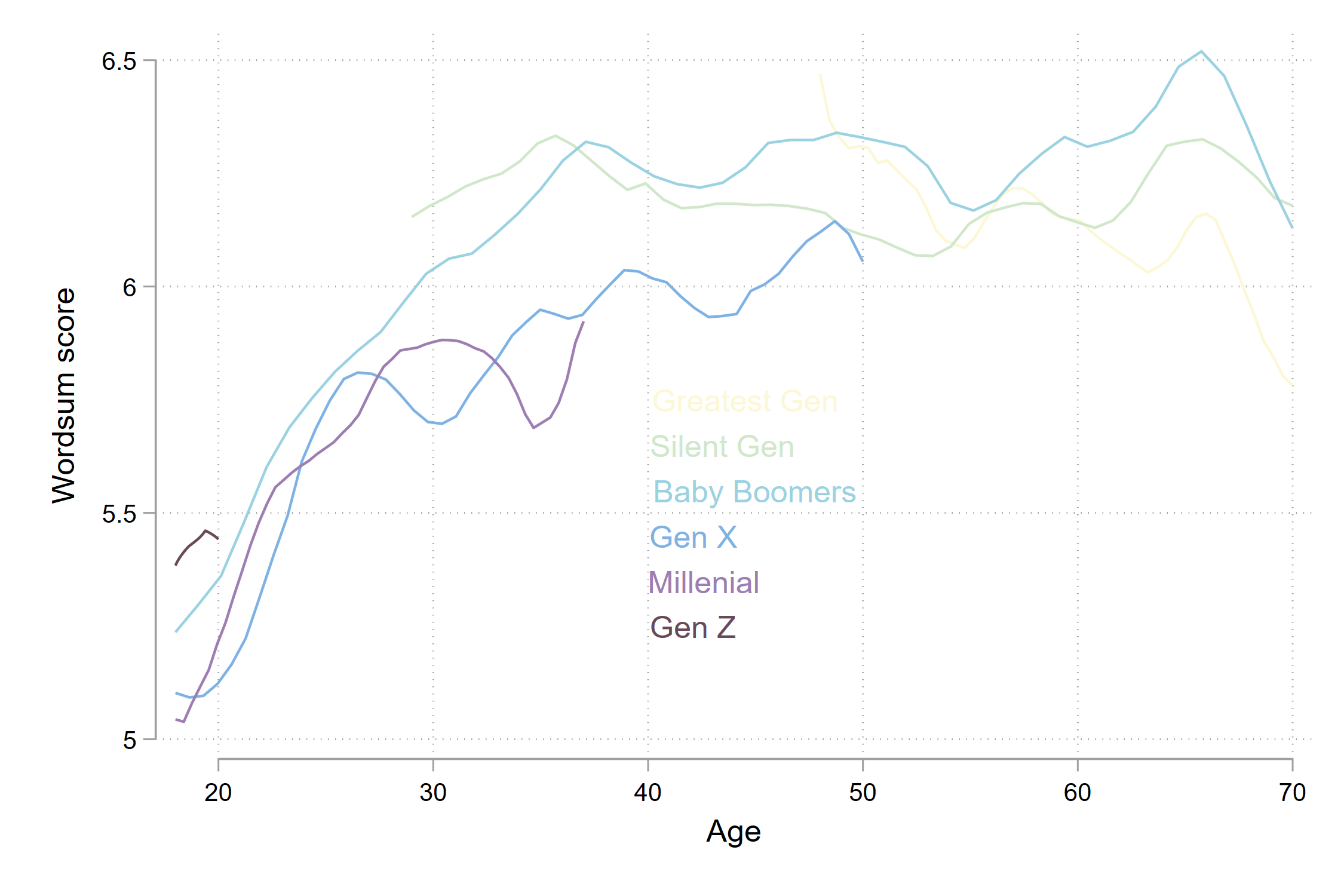

So let’s see what wordsum does across age. I’m just using the entire GSS 1972-2021, using survey weights, and computing local polynomial smooth plots to eyeball trends.

General Social Survey, 1972-2021, survey weights used to compute local polynomial. All respondents age 70 and younger.

Well, well well, this doesn’t look like the trajectory of fluid intelligence, does it!? Looks more like crystallized intelligence. That is, wordsum is probably more a vocabulary test, for my money.

Let’s also take a look at this graph. Wordsum scores increase by about a point, or ~10% of the total amount of change possible in the variable, between ages 20 and 40. So the linked tweet might well be measuring age differences and claiming them to be IQ differences.

Let’s look at the wordsum scores by age, by generation:

General Social Survey, 1972-2021, survey weights used to compute local polynomial. All respondents age 70 and younger.

1901/1926= Greatest Gen, 1927/1945= Silent Gen , 1946/1964= Baby Boomers , 1965/1980= Gen X , 1980/1995= Millennial , 1996/2003= Gen Z

What is there to write home about? It seems like there is not much difference at all among greatest, silent, and baby boomer cohorts. Gen X’ers converge by ~ 50, while Millennials seem to have fallen behind in their 30s (what a rude graph!). But the biggest gap we see is in, like, one decade of about 0.5 points. That’s hardly remarkable.

But here’s another thing: aren’t younger cohorts more diverse? And have more non-native folks? I’d assume that a growing proportion of ESL folks, as well as marginalized racial minorities, might introduce contrasting trends among these results. So let’s look at them separately by race. Sadly, I only see a racial variable that's “White, Black, and Other.” Let’s admit the major shortcomings of “other” and look at these groups separately.

General Social Survey, 1972-2021, survey weights used to compute local polynomial. All respondents age 70 and younger.

1901/1926= Greatest Gen, 1927/1945= Silent Gen , 1946/1964= Baby Boomers , 1965/1980= Gen X , 1980/1995= Millennial , 1996/2003= Gen Z

Heck yes, younger cohorts!! There’s barely any difference across white cohorts. It looks, to me, like black and other groups are increasing wordsum scores substantially across cohorts. In fact, it looks like there’s a smidge of convergence among Gen Z’ers. Woohoo! Go young people!! So I definitely think that there’s a lot of confounding going on, not just by age, but also by the issues that may arise with administering a 10-item vocabulary test to an increasingly diverse population.

There’s also been an increase in educational attainment over time. Let’s check that out. First, let’s look at the proportion of the GSS with a college degree across cohorts. We’re looking at folks aged 25+, so no Gen Z’ers.

General Social Survey, 1972-2021, survey weights used to compute local polynomial. All respondents between 25 and 70.

Big time educational expansion. College degree holders grew from 10% to 35% for white folks, 10% to just under 30% for “other” folks, and 5% to 20% for black folks. So massive expansion of education. What’s happened for folks with less than a college degree?

General Social Survey, 1972-2021, survey weights used to compute local polynomial. All respondents under 70

I see no change among white respondents, increasing wordsum scores among black respondents, and noisy growth-ish among “other” respondents, for folks without a college degree. So, improvement compared to what we saw in the original motivating figure.

What about college+ groups?

General Social Survey, 1972-2021, survey weights used to compute local polynomial. All respondents aged 22-70

For black and other groups, there’s no change across cohorts. We see a sizable decline of around one point among white cohorts, from around 8ish for Silent Gen folks to maybe 7ish for Gen Xers and Millennials. Not nothing. But considering the massive expansion of college education, a 1 point decline or no change is a pretty marginal shift compared to the 3x expansion of the college group. That is, much more selection in older cohorts. Who wants to bet that the top performing 1/3 of younger college cohorts would have better wordsum scores as the Silent generation groups?

So here are my big takeaway conclusions:

The graph Scott Alexander linked to probably reflected mostly the point that older people are older than younger people.

The graph probably represented the fact that a much larger share of folks go to college now than in the past.

Younger people are probably, at minimum, not dumber than their older cohort counterparts (I count people younger than myself as well).

Nevertheless, young people still need to improve on completing their readings before class and reading the syllabus.

Covid papers are dogecoin

I scribbled the idea at the end if this post in June 2021 and decided to sit on it. It represented my general skepticism of the booming covid paper industry. Ok, ok, I’m promising you that I actually wrote this one year ago. Perhaps the very not relevant anymore Dogecoin reference will increase my credibility here?

Well, John Ioannidi and his team have a new article in PNAS, Massive covidization of research citations and the citation elite.

Abstract: Massive scientific productivity accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic. We evaluated the citation impact of COVID-19 publications relative to all scientific work published in 2020 to 2021 and assessed the impact on scientist citation profiles. Using Scopus data until August 1, 2021, COVID-19 items accounted for 4% of papers published, 20% of citations received to papers published in 2020 to 2021, and >30% of citations received in 36 of the 174 disciplines of science (up to 79.3% in general and internal medicine). Across science, 98 of the 100 most-cited papers published in 2020 to 2021 were related to COVID-19; 110 scientists received ≥10,000 citations for COVID-19 work, but none received ≥10,000 citations for non–COVID-19 work published in 2020 to 2021. For many scientists, citations to their COVID-19 work already accounted for more than half of their total career citation count. Overall, these data show a strong covidization of research citations across science, with major impact on shaping the citation elite.

You see a massive citation bump of covid paper citations (purple dots).

From their conclusion:

COVID-19 papers published in 2020 received on average more than 8-fold the number of citations than non–COVID-19 papers and the difference exceeded 20-fold in General and Internal Medicine. Almost all of the top-100 most-cited reports published in 2020 across all science (not just biomedicine) were related to COVID-19, and the same applied to three quarters of the most-cited publications published in 2021. Many scientists received in a limited time high numbers of citations to their COVID-19 work and already have higher citations counts for COVID-19 alone than for all other scientific topics combined. Many authors who are highly cited for their COVID-19 work have had limited citation impact before the pandemic. COVID-19 is generating a new citation elite.

And:

Citation impact may not necessarily mean high quality or validity of the cited work. Many empirical evaluations of quality aspects of different segments of the COVID-19 scientific literature have consistently shown low quality (8–17). To our knowledge, there is no large-scale assessment of the correlation between quality scores (with all the difficulty of obtaining such scores) and citation impact of COVID-19 work specifically. However, other investigators have found that COVID-19 papers published in the most influential journals have weaker designs than non–COVID-19 papers in the same venues (14). Moreover, several extremely cited COVID-19 papers reflect topics that are debated or even refuted, such as editorials about the origin of the new coronavirus and early reports claiming effectiveness for interventions, such as hydroxychloroquine, that were not subsequently validated for major outcomes (e.g., mortality).

And:

As the total public funding for research is likely to change only gradually, and human productivity also has limits, it is plausible that persisting overemphasis on COVID-19 may reduce resources for other scientific work. This may have negative consequences on scientific progress, unless the imbalance in allocation is corrected promptly enough.

All considered, I think my much less thoughtful fretting below from last summer was pretty on the mark. Woohoo!

Wrote on 6/22/21, 7am. Drafting here. I’ll post at end of summer and see if I still agree.

Dumb hypothesis: most covid papers are academic dogecoin / gamestonk.

I was looking at google scholar today of prof's I really like and who do work on, let's keep this general, stratification.

They write awesome articles on substantive topics that get minor attention. cites: 20, 5, 17. Then along comes a 30-person slapped together covid paper on a totally unrelated topic. cites: 17million.

I saw this pattern 4-5 times without going out and looking for it.

My q: will papers like, "the networked facsimile of covid preparedness on reopening and the moderna vaccine" be of any substantive worth in 5 years? If you have a million cited toy paper totally outside your area...what value did you produce?

To me it's like: my car's repo'd but i have a dogecoin that cannot be turned back into money...i'm rich!

The kids are all right?

The other day I realized that students entering the university will have been born in 2003 or 2004. Besides making me feel extraordinarily old, I realized that they won’t have experienced many of the historical anchors that I have. They were born several years after 9/11. They probably won’t remember the Great Recession. I suspect that their political awakening will be the Trump/Clinton election. This is such a massively different social context than what I experienced. It’s weird to think that they probably feel about the Great Recession as I felt about the fall of the USSR/Berlin Wall. I was technically alive, but it wasn’t exactly on my radar.

I’ve assumed that young people were invariably progressive / left-leaning / members of the Democratic party, since that was my experience and seemed to have been pretty common since at least the countercultures of the 1960s. But the context these young people experienced is so different than mine, and I realized that I’ve never actually looked at any data.

So I opened up the GSS and tracked partisan attitudes among two groups of young people: 21-29 year olds, and folks 20 years old and under. Below are simple trends across birth cohorts between those born in 1945 and 2002 among the entire 1972-2021 GSS data. Color schemes are: blue=left/democratic, black=moderate/independent, red=right/republican.

Oh … weird. Ok, the top row are folks 21-29. The bottom row is folks 20 and under. The left column tracks folks who identify as Liberal/Moderate/Conservative. The right column tracks folks who identify as Democrats/Independents/Republicans.

Look at the bottom right panel. Me and the other glorious individuals born in the mid-1980s are the highwater mark of Democratic-identifying young people, at least among all those born after 1960. But since then, Democratic affiliation among under 20s has levels off, or slightly declined.

And look at what’s going on with under 20 Republican affiliation: an increase from about 25% in mid 1980s to almost 40% by those born in 2000. That’s not quite at the same highwater mark of ~ 45% among those born around 1970. But it’s close.

I don’t think there’s going to be a resurgence of Reagan youth. If you look at the bottom left panel, there was a moderate surge of conservative views among those born between 1960 and the mid 1970s. But that’s declined among recent cohorts. And among those born in the 1980s and afterward, liberal political views have increased and are about as high as at any time since the middle Baby Boomers.

…but … if we look at the previous Republican surge, there wasn’t a corresponding conservative surge…just a bump.

It also looks like young Republicans turn into slightly older Independents. And among 21-29 year olds, we can see a real and widening gap between growing liberalism and declining conservativism.

Let’s line up the views/parties affiliation to see if anything jumps out:

Democratic and Liberal rates tend to move in unison, compared to Ind/Mod and Rep/Cons. We see the boom/bust of Republican affiliation among young people pretty uncoupled from conservative views. And the booms of partisan waves (Reaganite Gen-Xers, Democratic Millennials) are much easier to see in the under 20 ages than in the 21-29 ages.

It’s still a tad hard for me to see what’s going on here. Let’s line up under 20 and 21-29 trends to see how cohort political views change as cohorts age.

Here we’re looking at party affiliation. Dashed lines are percent of folks under 20 affiliating with particular parties. Solid lines are 21-29. These values are lined up by birth year, so if there’s a large gap between lines, that means particular cohorts became more / less Democratic / Independent / etc.

We see that Gen x-ers, early Millenialls became much more affiliated with the Democratic party in their 20s. There’s not much difference for the younger Millenialls. And maybe some more growth among the oldest Gen Z’ers.

We see some wild stuff for Republican affiliation among young Milliennials / old Gen Z’ers. Massive decline of Republian affiliation in 20s compared to under 20. Looks like maybe a lot of switching to Independent? We see Baby Boomers became more Republican leaning in their 20s, while Gen-X’ers declined substantially in their Republican affiliation in the 20s.

Here we’re looking at partisan views. Lots of fluctuation for liberal values. Baby Boomers became less liberal in their 20s, Gen X-ers became more liberal in their 20s, Millennials less liberal in their 20s, and Gen Zer’s more liberal in their 20s. This all ocurrred with 20-somethings becoming increasingly liberal after a massive decline among the Baby Boomers.

Look at Conservatism. Few things have become less popular among 20-somethings since the beginning of Gen X than conservative views. It’s about as low among today’s 20-somethings as it’s ever been. At the same time, “Moderate” has steadily increased among 20-somethings. Until Gen-Z, cohorts tended to become less moderate as they transitioned into their 20s. But there’s been convergence in recent cohorts, so that in the most recent cohorts there’s no real difference in Moderate viewpoints between under-20s and 21-29'ers.

I draw 3 main conclusions:

2010 onward Republicans completely squandered an amazing opportunity to channel a Right-wave of young people into a new cohort of Republican voters. Massive fumble. It looks like a rising wave of under 20 Republicans vanished as these folks aged. The gaps between a cohort’s youth affiliation and 20-something affiliation is larger than anything else I see in these data. Is this a college thing? A Trump thing? Unclear.

I see a lot less certainty about a steady march leftward among young people. Sure, 20-somethings are increasingly liberal. But this isn’t really translating into Democratic party membership. I’d rather characterize the left / Democrats as someone who took a step forward to pick up a nickel and a piano fell where they were previously standing. Basically…alive because of dumb luck and not much else. “Independent” and “Moderate” are dark horse winners. And historical fluctuation seems to be the rule. Not a steady movement one way or another. I think anyone waiting around for cohort replacement will probably be disappointed.